As an instructional designer, it is prudent to have a methodology in place to design effective instruction. Recently, I reviewed several design resources which have helped to shape the methodology that I employ as a designer:

- Leaving ADDIE for SAM: An Agile Model for Developing the Best Learning Experiences by Michael Allen

- Principles of Instructional Design by Robert M. Gagné, Leslie J. Briggs, and Walter W. Wager

- The Conditions of Learning: Training Applications by Robert M. Gagné and Karen L. Medsker

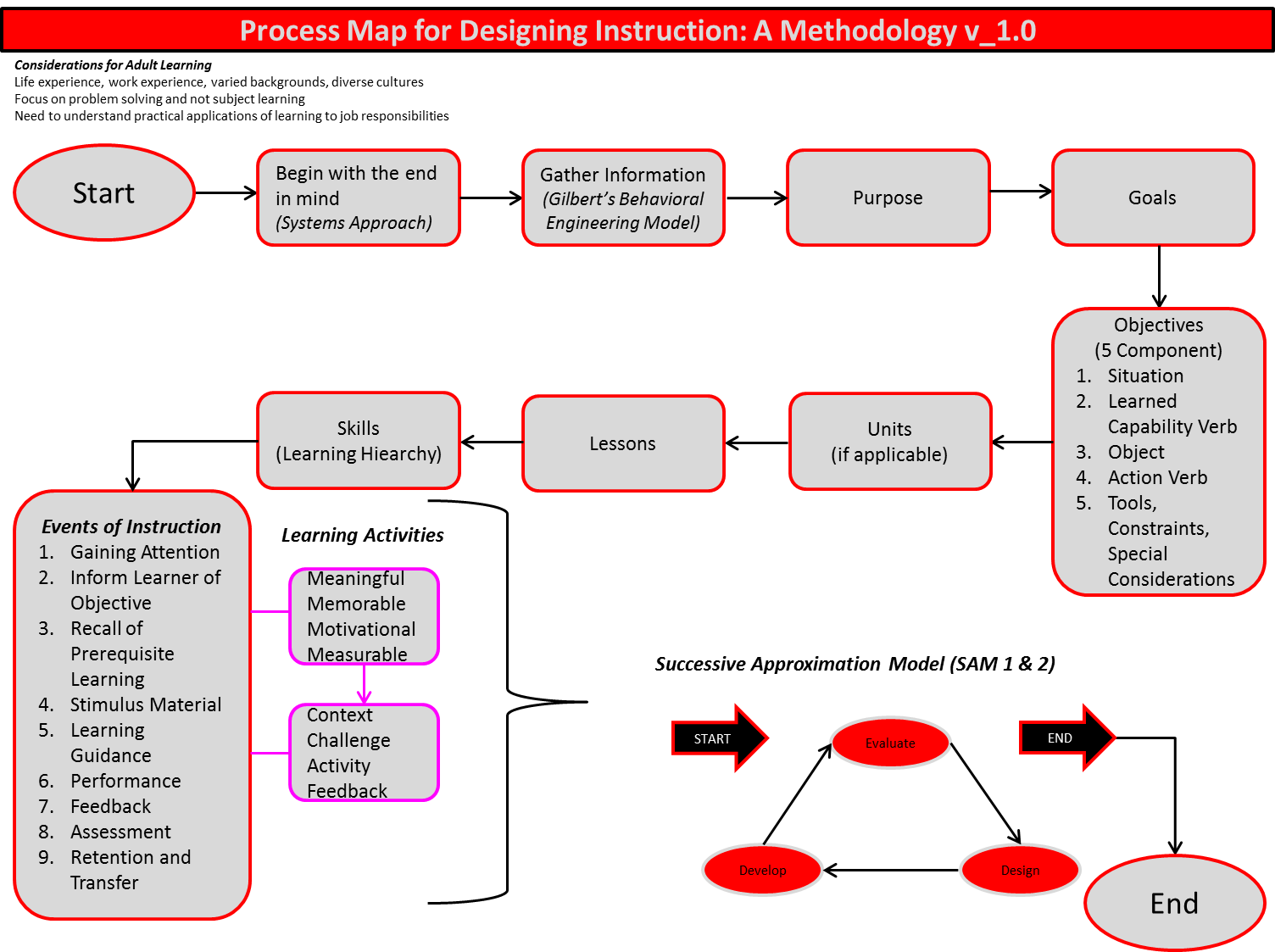

To synthesize what I learned from the aforementioned sources, I created a process map for how to design instruction illustrated above.

Begin With the End in Mind

To design effective instruction it is best to begin with the end in mind. The instructional designer must take into account the knowledge, skills, and abilities that the learner must know and be able to do upon completion of a given course and create relevant course goals and objectives. Course goals and objectives drive the course design, and this is considered a “systems” approach to instructional design. Under this philosophy, good course design should not turn learners into subject matter experts by emphasizing content and coverage. Instead, well-designed courses show learners the practical applications of what is to be learned. The instruction, therefore, relates these applications to learner job responsibilities so that the learner sees the value in receiving the instruction.

Gather Information

Beginning with the end in mind means gathering information about what the learners are expected to know and be able to do on the job. Sources for information include but are not limited to project sponsors, subject matter experts, supervisors, trainers, learners, training manuals, review guides, and performance reviews. In gathering information, the instructional designer works to determine reasons for a performance gap between actual job performance and desired job performance. A helpful model for sorting out performance related issues is Thomas Gilbert’s Behavior Engineering Model. Do the performance issues result from lack of expectations and feedback? Or are they a result of a shortage of tools and resources? Or are they a result of the absence of consequences and incentives? Or are they the result of deficiencies in worker skill and knowledge or incorrect worker selection and assignment or misaligned motives and preferences? If the performance gap is insignificant, designing a course and putting people through a learning event may not be needed. For instance, performance issues may be remedied by more direct and clearer communication, a job aid, or a brief video tutorial series, etc. If, however, this gap is significant, then designing a course that will help improve job performance may be necessary.

Purpose

If it has been determined that there is a significant gap between actual performance and desired performance and that the solution to closing this gap is a course of instruction, the instructional designer, taking into account the information that has been gathered, must define a course purpose. A course purpose is not a description of course content. Rather, it is a statement of what the learner will learn and be able to do after having taken the course.

Goals

As a course purpose defines what a learner is going to learn, the goals of the course state what the learner must do in order for learning to take place so that the course purpose may be fulfilled.

5 Component Objectives

Course goals are broken down into course objectives. Course objectives are observable measurable behaviors that when mastered move a learner toward the achievement of a learning goal. They specifically state what the learner will be able to do as a result of instruction. Gagné, Briggs, and Wager suggest that a well written objective has five components:

- Situation—describes the situation or context in which the learner’s performance is to take place

- Learned Capability Verb—Used to classify a learner’s performance outcome (discriminates, identifies, classifies, demonstrates, generates, adopts, states, executes, chooses)

- Object—Indicates the content of the learner’s performance

- Action Verb—Indicates observable behavior through a description of how the learner’s performance is to be completed

- Tools, Constraints, or Special Conditions—Specific equipment, temporal considerations, or number of attempts that a learner must perform with or under

(Gagné, Briggs, and Wager 1988, 123-125)

Organization and Breakdown of Objectives

Course objectives should be organized and grouped into units based on relevance, sequence, or similarity. Each objective in a unit becomes the basis for a distinct lesson. Lessons allow the learner to focus on the mastery of a single objective. To aid the learner in the mastery of a lesson, single objectives are further broken down into the skills required to master the lesson objective. The required skills are taught to the learner and mastery of them moves the learner toward mastery of the lesson objective and in turn toward achievement of course goals.

Events of Instruction

With course purpose, goals, and objectives established and course objectives organized into units and lessons the instructional designer can begin to plan the learning activities for each distinct lesson. The basis for this planning is Gagné’s nine events of instruction. The nine events of instruction are designed to support the learner in their mastery of lesson objectives. In addition, they serve as a guide for what components the instructional designer should include to create an engaging and effective learning activity. Gagné’s nine events of instruction are as follows:

- Gain the attention of the learner

- Inform the learner of the learning objectives

- Stimulate recall of the learner’s prior learning

- Present content to the learner

- Provide the learner with learning guidance

- Elicit learner performance

- Provide the learner with feedback

- Assess learner performance

- Enhance learner retention and transfer

(Gagné and Medsker 1996, 138-149)

It is not always necessary for the instructional designer to include all nine events in the creation of a learning activity. It is, however, per Michael Allen, necessary for the instructional designer to ensure that the learning activities are meaningful, memorable, motivational, and measurable. In other words, the learning activities must allow the learners to connect new content to prior knowledge and skills (meaningful); the ability to practice and perform new knowledge and skills learned (memorable); the opportunity to learn, retain, and apply new knowledge and skills (motivational); the chance to practice and receive performance feedback (measurable). In addition, it is also necessary for the instructional designer to ensure that the learning activities offer the right amount of context, challenge, activity, and feedback. That is, presenting the situation and conditions a learner must take into account when performing a task (context); allowing the learner to re-examine the context and fully consider the probable outcome of various responses (challenge); designing the learner’s task so that it looks and feels similar to the real tasks learners are expected to actually perform post training (activity); communicating to the learner the consequences of what would really happen in response to learner action or inaction (feedback).

Successive Approximation Model

The process of designing a course and the corresponding learning activities must be iterative. An iterative process allows for frequent evaluation and correction of course and activity design which can be reversed or modified several times. Allen’s Successive Approximation Model or SAM is an example of an iterative design process. In the first iteration the instructional designer analyzes client needs and goals (evaluate); prepares a rough draft of the course or learning activity that is to be discussed with stakeholders (design); prepares prototypes of the course or learning activity to give the stakeholders a sense of look and feel (develop). In each successive iteration, the success of the previous iteration is determined (evaluate); refinements are made or new alternatives are sketched out (design); prototypes become more representative of the final product (develop). The objective of iterative design or SAM is to give the stakeholders and the instructional designer the latitude to make amendments as course or activity design unfolds so that when the course or activity design is complete the course or activity is effective in meeting the needs of the learners and the stakeholders.

Thoughts and comments are welcome.

References

Allen, Michael. 2012. Leaving ADDIE for SAM: An Agile Model for Developing the Best Learning Experiences. East Peoria, IL: Versa Press.

Gagné, Robert M., Leslie J. Briggs, and Walter W. Wager. 1988. Principles of Instructional Design. 3rd ed. Fort Worth, TX: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, Inc.

Gagné, Robert M., and Karen L. Medsker. 1996. The Conditions of Learning: Training Applications. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Group/Thompson Learning.

Gilbert, Thomas F. 2007. Human Competence: Engineering Worthy Performance. Tribute ed. San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Leave a Reply